Grafting Lemon Trees – How to Graft a Lemon Tree with the T-Bud

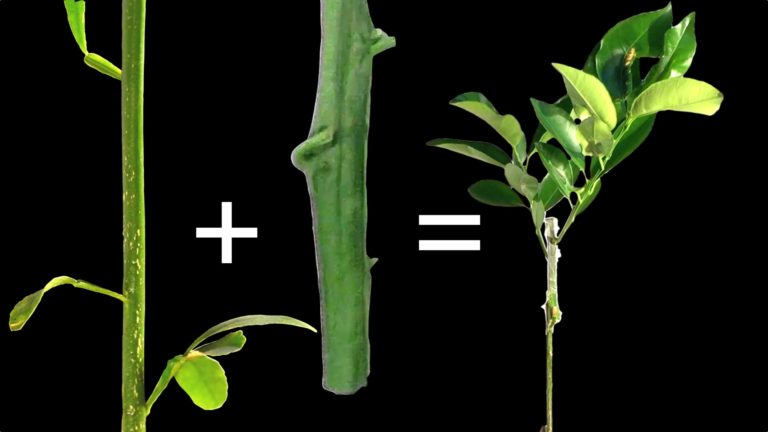

This step-by-step guide shows how to graft a lemon tree using T-budding, a technique for grafting lemon trees that is easy and that gives a high success rate. In T-budding a single bud from a desired variety is grafted onto a rootstock. The T-bud is one of the most common methods used by nurseries to graft lemon trees. In addition to its use in lemon grafting, T-budding is also used for grafting fruit trees of many kinds.

In order for the T-bud to work, it must be performed during a time of the year when the tree is actively growing and thus the bark is slipping and can be peeled back easily. The ideal lemon grafting season depends upon local temperatures. In my California climate, the T-bud can be used for grafting citrus in summer and in late spring. In times of the year when the bark is not slipping, the chip bud can be used instead. T-budding is commonly used to propagate new trees. Some people use the T-bud to topwork trees or to make multi-fruit trees, but for these grafts I prefer patch budding, cleft grafting, or bark grafting.

Grafting Lemon Trees – How to Graft a Lemon Tree with the T-Bud — YouTube Video

In addition to this step-by-step guide to grafting lemon trees, I have also made a YouTube video (see below) showing how to graft a lemon tree with the T-bud.

Citrus Budwood from a Disease-free Source

Citrus cuttings have the potential to spread tree-killing diseases. It is often not apparent when a tree is infected with a fatal disease. This makes the source of citrus budwood for grafting very important.

In California we now have both exotic diseases that kill citrus trees and also the insects that spread the diseases. The situation is so severe that it now against the law in California to graft with cuttings taken from backyard citrus trees. To save our trees from deadly diseases, hobbyists in California no longer swap citrus cuttings with friends. We now instead order our budwood at a nominal cost from the Citrus Clonal Protection Program (CCPP), a program that exists to provide disease-free budwood for the grafting of citrus trees.

The CCPP will ship budwood anywhere in the world where the local government allows it. Many citrus growing regions where CCPP budwood is not allowed have their own disease-free citrus budwood programs. Here I have created a web page that lists some other programs: Citrus Budwood Programs.

The below YouTube video goes through in detail the process of setting up an account and placing a budwood order with CCPP.

Disinfecting Grafting Tools

In order to both maximize the probability that the graft lives and also to prevent the spread of disease from tree to tree, it is important to disinfect grafting tools between grafts. To learn more about disinfecting grafting tools, please see the following link: Disinfecting Grafting Tools.

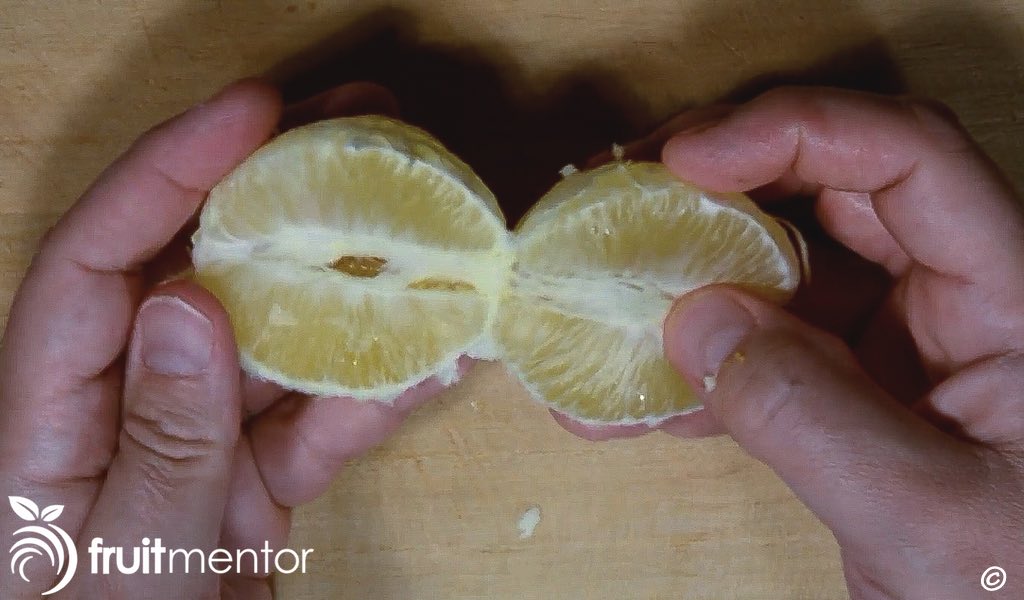

Grafting the Lemonade Lemon Hybrid

The fruit grafted in this article is the lemonade lemon hybrid. I first learned of this fruit in 2014. It has been recently released by the CCPP. It is unlike any other lemon that I have tasted. It is neither sour like a typical lemon nor bland like an acidless lime. It has a balance between sweet and sour like an orange, but it tastes like a lemon. It can be peeled and eaten like an orange or squeezed for its juice. The lemonade fruit is delicious and is a favorite in my family.

Rootstocks affect Fruit Characteristics

My first experience with the lemonade lemon was a fruit from a tree at the CCPP that had been grafted on Citrus macrophylla, a rootstock typically used in California for lemon tree grafting. I noticed that many of the fruits on the tree were dry on the inside, but the ones that were juicy had a pleasant flavor. Since rootstocks impact fruit characteristics, I theorized that Citrus macrophylla might be the wrong rootstock for lemonade. I was unable to find any reference that indicated the correct rootstock, so I decided to use carrizo, a rootstock that is often used for grafting orange trees. I have since sampled lemonade fruit from trees that were grafted on carrizo and on C-35 and can confirm that both of these rootstocks do produce superior lemonade fruit.

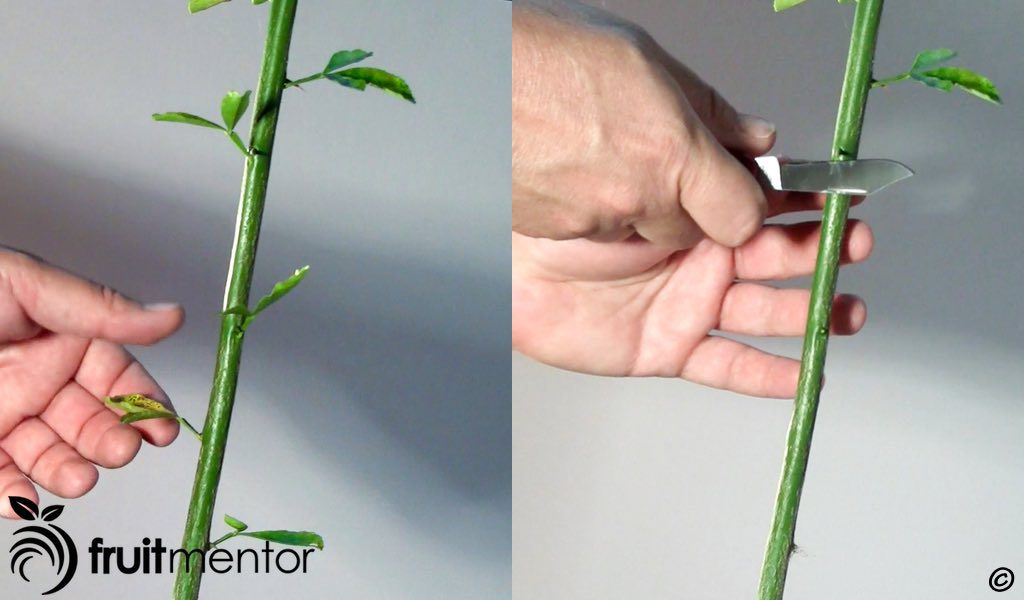

Preparing the Rootstock

To prepare the rootstock, I remove the leaves and thorns at a height around 8 to 12 inches or 20 to 30 centimeters above the soil. A tree grafted at this height will be less disease-prone than a tree grafted closer to the ground.

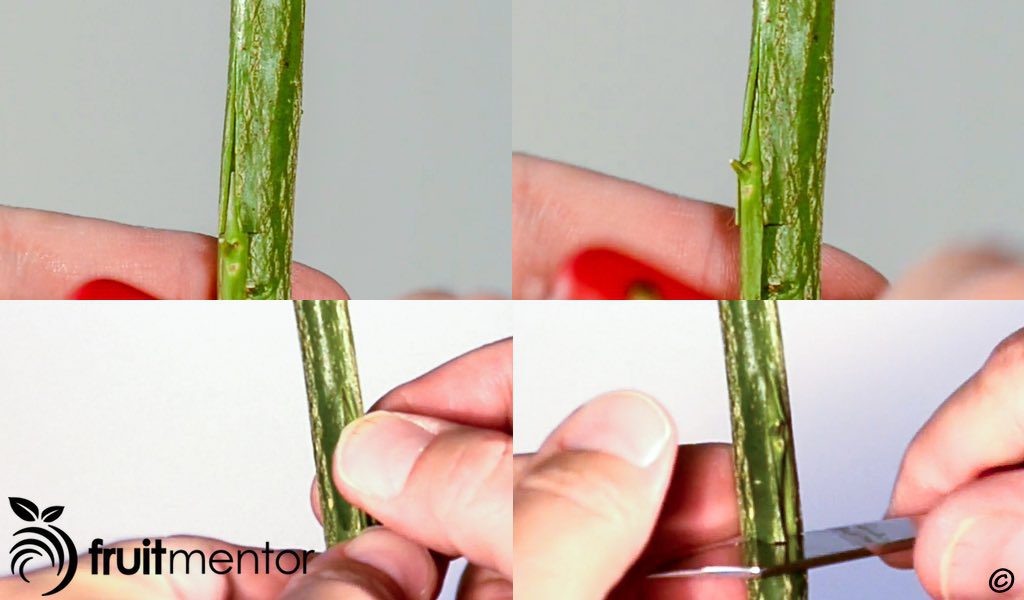

Cutting the T

I cut an upside-down T into the rootstock. An upright T will also work. The advantage of an upside-down T is that it can help to keep water out. That is not important to me in California's Mediterranean climate, but it may produce better results for those in rainy climates.

After pressing the knife into the bark, it will stop when it hits the wood. The knife only needs to cut the bark and does not need to cut into the wood, so it does not require much force to make the cut.

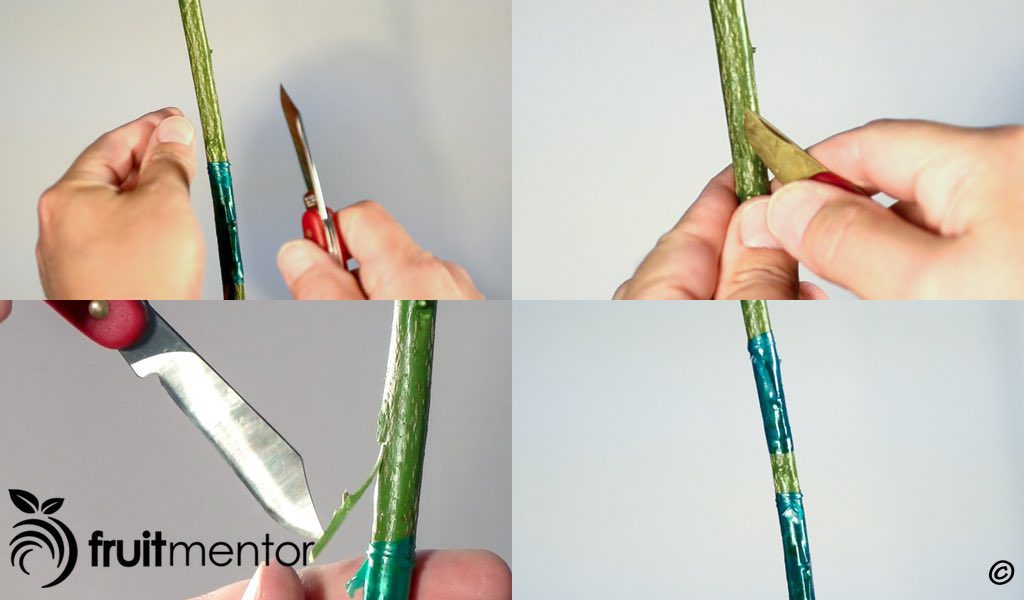

Peeling the Bark Back

Next I peel the bark back with the bark lifter on my grafting knife to prepare the rootstock to receive the bud. If the bark does not peel back easily it may be the wrong time of year for T-budding and the chip bud may be a more appropriate graft.

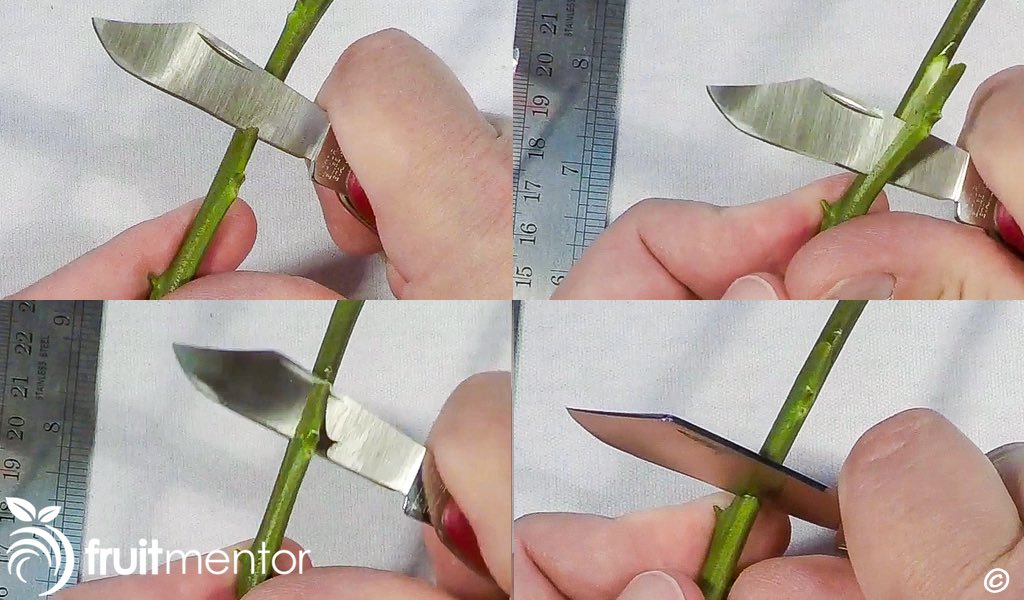

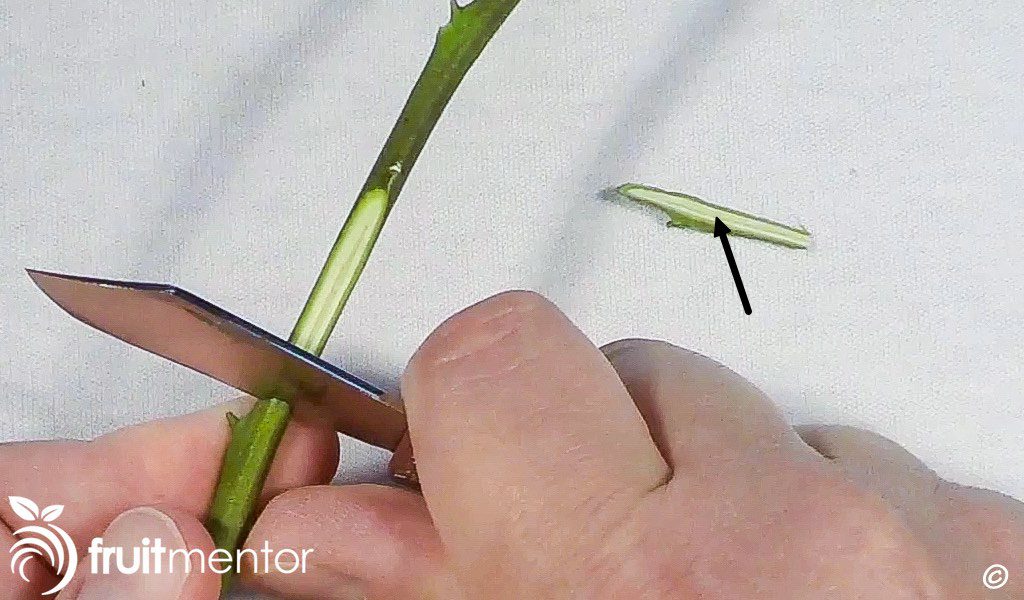

Cutting the Bud

I slice underneath the bud with my knife almost parallel to the budstick. I withdraw my knife and then make a second cut to remove the bud from the budstick.

The wood on the back of the bud does not need to be removed.

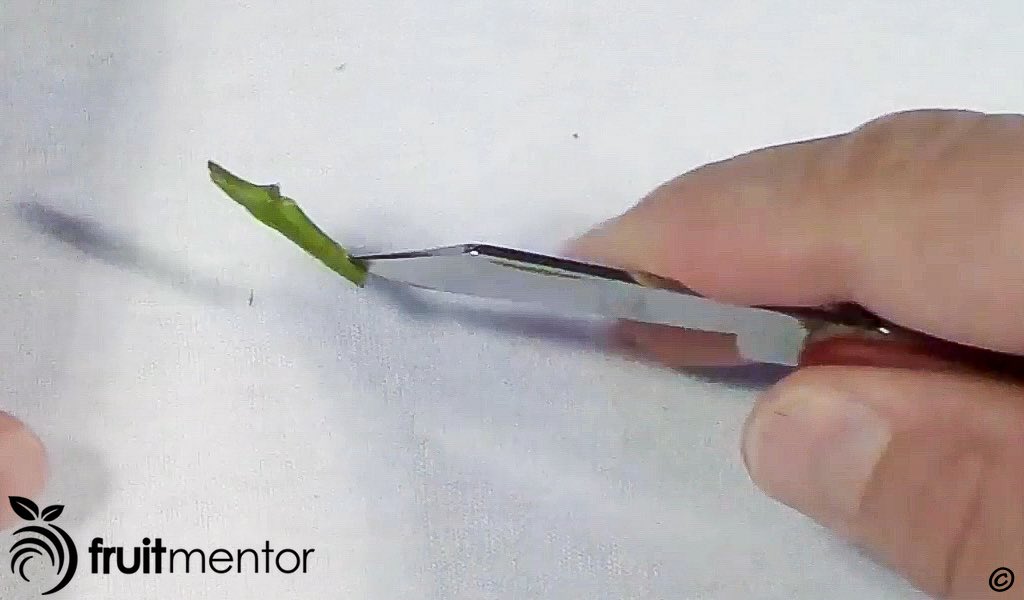

Handling the Bud

It is important to avoid touching the cut surfaces of the bud. It is often possible to hold the bud by the petiole where the leaf was attached. Since this convenient handle has has fallen off, I pick up the bud with my knife.

Inserting the Bud into the Rootstock Incision

Next I insert the bud piece under the bark flaps and push it up into position. The bud piece was longer than my incision in the rootstock, so I cut off the portion that was sticking out.

Orientation of the Bud

It is important to graft the bud right-side-up. The bud should be on top and the scar where the leaf was attached should be on the bottom.

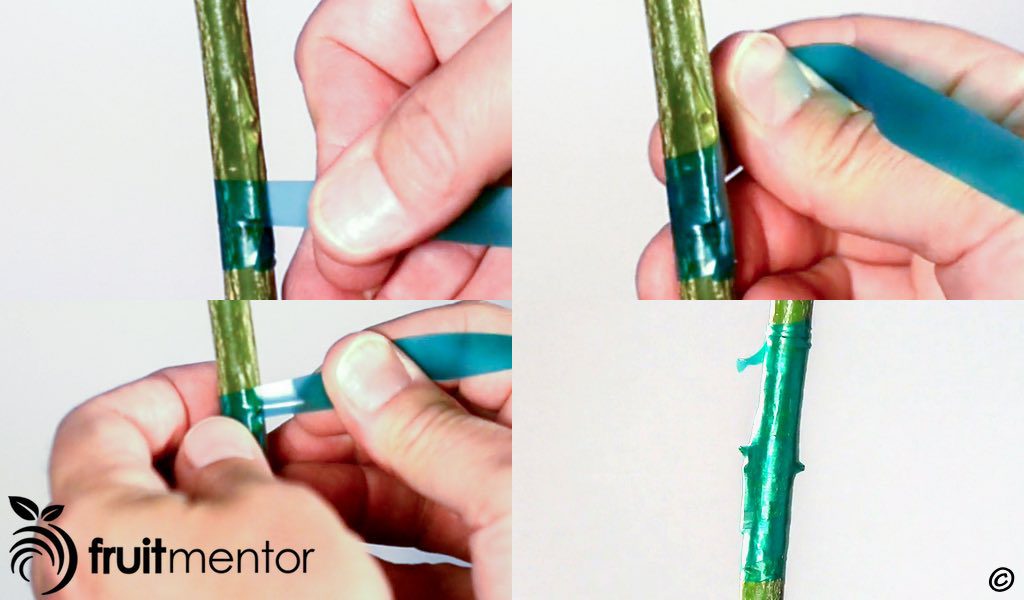

Wrapping the Bud

Next I wrap the bud tightly with vinyl tape, starting below the bud and wrapping up. Vinyl tape is a good wrapping material for the T-bud because it can be stretched tightly without breaking. I have attempted T-buds that failed because I did not have vinyl tape on hand and substituted parafilm. The bark flaps lifted up and broke through the parafilm causing the grafts to fail. Since the cost of a roll of vinyl tape is lower than the cost of a budstick, it would have saved me money and time to buy the vinyl tape.

I have a web page on grafting supplies and tools that shows where to buy vinyl tape and other tools such as saws and grafting knives. It can be found here: Grafting Supplies and Tools.

Grafting a Backup Bud

In order to improve my chances of success, I like to graft a second bud to the rootstock. This way I will succeed even if one of the bud grafts fails. Professional grafters have a high success rate and would not waste time doing this. They typically graft a new bud when they have a failure. It makes sense for a hobbyist, however, as it can save time in case a bud fails to take.

Healing the Grafts on the Grafted Lemon Tree

After the grafts were finished, I moved the grafted lemon tree to a shady area for a three week healing period. After the healing period, I unwrapped the grafts and found that they were both green, an indication of success.

Planting the Tree

I would normally plant a grafted lemon tree after the graft had grown in the container. My family likes lemonade fruit so much that I planted the tree in the ground before forcing the graft to grow. Citrus trees do much better in the ground than in a container, so planted the tree to get it off to a better start.

I let the tree settle in for a few days before proceeding to next step.

Forcing the Bud to Grow

When grafting trees it is important to understand a phenomenon known as apical dominance. Apical dominance governs the growth of all buds on a tree including the grafted buds. Natural hormones from buds at the end of the branches prevent buds lower down from growing. In tree grafting, the effect of these hormones must be overcome in order for the grafted buds to grow.

I break apical dominance by cutting halfway through the rootstock and pushing it over so that the terminal buds are lower than the newly grafted buds.

Growth of the Bud

These photos show about three weeks of growth. The bottom bud began to grow before the top bud.

Removing the Top of the Rootstock and Staking the Tree

After a bit more growth, I removed the top of the rootstock and staked the tree.

Removing Rootstock Suckers

When grafting lemon trees with the T-bud, the process of breaking apical dominance commonly causes buds on the rootstock to grow in addition to the grafted buds. The following spring, I had a rootstock sucker that almost overtook my lemonade graft. For all grafted fruit trees it is important to remove roostock suckers. When I removed the rootstock sucker, I also pruned off the tip of the lemonade graft to again break apical dominance and encourage branching.

Lemonade Tree after more Growth

Here is another photograph of the lemonade tree showing the new branches.

Save Trees by Sharing

Please share this article with anyone that you think may be interested in grafting lemon trees or grafting citrus trees of any other variety. Knowledge of the importance of using a registered disease-free budwood source when grafting citrus will help to prevent the accidental spread of deadly citrus diseases and will save trees.

Resources for Californians

Please visit CaliforniaCitrusThreat.org for more information on how to stop the spread of deadly citrus disease.

California Law Regarding Citrus Propagation

In California, the collection of any citrus propagative materials, including budwood and seeds, from non-registered sources is illegal. Any citrus trees grown or grafted in California must come from source trees registered with either:

- The Citrus Nursery Stock Pest Cleanliness Program, administered by the California Department of Food and Agriculture, or

- The Citrus Clonal Protection Program, located at the University of California at Riverside.

Funding

This article was funded by a grant from California’s Citrus Research Board.